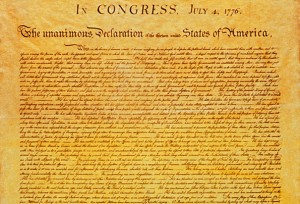

I’m going to indulge my arrogance and pretend I know better than others. It’s a thing I do, sometimes, because my head is full of thoughts and I have to shove them out like a hoarder needs to shove the debris out of his home, if only to make room for more. So, what I’m going to do is, I’m going to parse the Declaration of Independence. Saturday is Independence Day, so it’s a good time to remind people why we felt we needed to be our own country, and some of the ideals we hoped the new one would espouse.

A lot of people forget that, while the Declaration is definitely one of the founding documents of our nation, nothing in it, except the Declaration of Independence from the British Empire has the force of law. All of the lofty phrases and brilliant ideas are statements of philosophy only. Ways for the drafters to lay down, on paper, the driving principles they hoped the new nation would embrace and embody. So, let’s get started:

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

In these days of no-fault divorces and lifelong relations dissolved over Facebook comments, it’s hard to remember that, once upon a time, it was considered unthinkably rude to close the door on a relationship without explaining why it had to end. The Signers of the Declaration were mindful of this, and drew up this outline of grievances to show the world that they were not merely petulant children using the threat of independence to get special treatment for their colony.

This was the Second Continental Congress, and both this one and its predecessor had sent letters of redress to the Crown and to Parliament. Shots had already been fired in anger before this Congress met, and, even though they agreed to organize a defensive force under George Washington, they still hoped, at first, that there might be some sort of reparation.

This was a Dear John letter. “Dear England, We’re sorry. We tried, we really did, but it’s just not working out. This is why we have to leave. If the reasons sound familiar, it’s because they’re the same things we’ve been saying for five years.”

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,

Let’s take a moment, here to snuff out a stupid debate I’ve heard from time to time. All of these men, with the possible—possible—exception of Benjamin Franklin, were Christians. They were not modern evangelicals, but they did believe in, and at least give lip service to, the Christian God. Most of them held a Deist version of the faith, that is they believed that God was out there, somewhere, probably, but didn’t consider God to be concerned with individual lives, or even the current state of the world.

There were a few reasons for this. The Calvinists among them believed that God had set everything in motion on an imperturbable path and every choice, every decision was already written down and accounted for. For the most part, others believed that, in order to be worthy of God’s Great Kingdom, they had to show that they could handle man’s little kingdom well enough. They all thought about God, but in an abstract, the way people who live in Eastern Colorado think of the mountains that loom ever on the western horizon.

And they were from a number of different denominations. Most were Anglican (or Episcopal, if you prefer), some were Methodist, Baptist, Lutheran, or Presbyterian. A few were Catholic. Franklin was raised a Friend (Quaker), but his writings at the time suggest that he was agnostic, at best.

Excepting the Anglicans, most of them (or their ancestors) came—or were sent—to the Colonies because they were either persecuted or disenfranchised at home. That is why God is mentioned exactly twice in the entire document, and in vague, general terms.

Each man had his own belief, but however deeply he felt it, he felt that his needs, and the needs of his neighbors and country, were better served by his allowing that others might see the world differently. Even if he thought they were wrong in their faith.

that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.

Earlier drafts replace “pursuit of happiness” with “security of property.” It’s open for debate whether Jefferson changed it on his own, or whether the other drafters thought mentioning property so directly was crass. In any case, the vague, but lofty, phrase is the one we have.

The first two seem simple enough by comparison. Human life is marked as sacrosanct from the first book of the Bible. The first Sin may have been Disobedience, but the first Crime was Murder. These men firmly and deeply believed that it was morally and religiously wrong for one man to kill another, without cause, And even more so for a government to do the same.

But these men weren’t naïve, either. They knew they were entangled in a bloody war with potentially disastrous consequences. Several battles had already been fought, most notably at Breed’s Hill and at Lexington and Concorde. Even as they argued over the placement of commas, Washington was beginning preparations to meet a massive landing at Manhattan. They knew that all men die. They also knew that sometimes, men’s lives had to be taken.

What they meant by a right to Life was that no government had the right to round up “instigators” and hang them without a trial, that assassination of political or philosophical enemies—whether with a sniper’s bullet or an explosive-laden drone—didn’t hold water no matter how many times you shouted “clear and present danger.”

You have the Right to Life. Every person has the right to expect that, as long as they obey the rules that allow humans to live together, they will not have their life taken from them by their government or their countrymen.

By the same token, Liberty is also not as easy as it seems. The Feudal system was not that far gone in England, and it thrived, in one form or another, in Ireland, France, and Central and Eastern Europe. Liberty, for these men didn’t mean Licentiousness. It didn’t even mean the amazing array of rights and privileges we modern westerners take for granted every day.

For them, Liberty was a simple thing. It was the right to move about and establish a family, or a business. It was the right to speak your mind about the state of things, and to meet with others who agreed or disagreed with you. It was the right to know you couldn’t be imprisoned for your faith, or your family’s name, or because you fell on hard luck. Liberty, for the drafters of the Declaration, was freedom from literal, unbending chains.

“But what about slavery?” you ask. That’s a tough and troubling question, and it was one many members of the Congress wrestled with at the time and for years to come, most notably Jefferson. He was caught between the mill and the millstone. He hated slavery, had written against it many times, but he owned slaves, because his wealth and livelihood, and that of his children, depended on a system where slavery was not only widespread, but necessary for success.

Others, especially those delegates who were Friends, had similar morally and ethically shattering concerns. How could they speak so blithely about the “unalienable right to liberty” when thousands of men were deprived of that very liberty every day.

Sadly, sometimes morality has to bow to reality. Jefferson never freed his slaves in his lifetime for the same reason that the parts of the Declaration that mention slavery were excised. All of the money, and most of the population, at the time of the Signing, was in the South. New York was staunchly Loyalist, and no one believed that setting the seat of government there was going to change more than a few, easily swayed, minds. They needed the South if they were going to succeed in their rebellion, and the South came with baggage. Baggage that would eventually nearly destroy us.

Finally, we have “the pursuit of happiness”. It’s a phrase, not a word. As I mentioned, above, the original phrase was “security of property.” Like the other two unalienable rights, the original term is reinforced in the Bill of Rights, and given the force of Law, but the final term?

And it’s the pursuit of happiness. Odd that the drafters don’t say that everyone has a right to be happy, only the right to pursue happiness. Like Liberty, this one needs to looked at with a sideways eye.

It may just be that they knew that some people aren’t going to be happy, and raising the idea of universal happiness to the status of unalienable right was a little too hippy trippy even for avid students of the Enlightenment. Maybe it comes down to the fact that bad luck is going to happen, but you have the right to take your chances.

Maybe it was code. Speaking of property as a desirable thing is crass, but all of these men were either self-made or only one or two generations from those who were. Maybe “pursuit of happiness” means the right to invest, to own property and know it is secure, to pass your wealth on to your progeny. Maybe “pursuit of happiness” really means freedom from imposed misery.

More tomorrow.