Okay, I went a little off on the responsibility of free people to maintain a free society in the last bit, but now we’re getting into the colonists’ specific complaints against the King.

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

Oh. Hmm… So it turns out that they weren’t the hot-headed firebrands they might, at first, appear to be. This sentence basically says, “We admit that it’s stupid to knock it all down and start over if it can be fixed.”

And that sentiment is valid today. More and more I read about petitions and calls for a variety of new constitutional amendments from those seeking to counter the ridiculous conclusions of the Citizens United decision to the recurrent calls for a “balanced budget” amendment. The thing is, Supreme court decisions are mere interpretations of law and are often overturned, Plessy v Ferguson being the one that springs first to mind.

The 18th and 21st amendments should both stand together as solid examples of why it is a dumb idea to use the Constitution as an instrument to create rules too specific to circumstance. And why any change to the foundation of our country must be one of necessity and not momentary whim.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their further security.

And we’re back to what we were talking about yesterday.

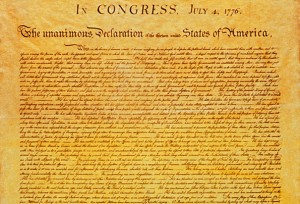

Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

The colonists’ real beef was with Parliament, not the King. You will find nobody on the planet who will tell you that George III was in any way a tyrannical monarch or even a particularly active one. However, it was easier to publicize and cement public support against the Evil Dictator King than Parliament Trying to Pay Off the Seven Years War Debt While Expressing their Right to Govern the Colonies. Sound familiar?

I’m not saying they were making shit up. The specific complaints (which I’ll get into tomorrow) were real and valid. I am saying that it was neither as simple, nor as black and white as they made it sound, or as we Americans like to believe.

The trouble started with the French and Indian (7 Years) War. Depending on who you ask, that war was the direct result of the French encroaching on Colonial lands, Colonial speculators seeking new profitability from the recently-opened Cumberland gap, or British Imperialists seeking to expand British territorial claims in the New World. Whatever it was (my vote goes to all three in an amusing international cocktail I like to call a Murderita because it always starts with a bunch of festive nationalist songs and ends with someone burying half their family while facing a Mastercard charge they can’t quite remember accruing), the war was expensive, and the homeland felt that the colonies should shoulder some of the expense since much of it was incurred on their behalf.

This led to a number of new taxes, mostly aimed at the North American colonies. Mind you, most of the colonists, while not in love with the new taxes, just shrugged and started paying them. The New England colonies, however, who depended on trade for their livelihood, protested against the taxes. I should point out that when I say “protested,” I mean a drunken mob marched violently through town threatening and bullying anyone who didn’t agree with them. These protests often ended with a crudely-made effigy of the King (or, more likely, some local official) being hung and/or burned.

The most famous of these, the Boston Tea Party, was less a protest than a frat prank. Contrary to impressions, they didn’t sneak onto the ships, they were allowed on by the guards who saw right through the clever “Indian” disguises worn by the Sons of Liberty and may have greeted some of the members by name. It took them all night, by which time, they were almost certainly sober, but, by then it had become a macho thing, and they continued dumping the taxed tea into the harbor, grimly scooping it up and re-dumping it when the dump pile overwhelmed the ship’s gunwales. Later, the richer sponsors of the act paid for the tea (tax and all).

Parliament repealed most of the more obnoxious taxes, but because you can’t get five humans together without at least a little dick-waving, they passed other acts to show the Colonists that they were still in control. Then they passed the Stamp Act, which, besides being a dumbass tax on all paper products, including newspapers and spittle-emitting screeds, was extremely annoying to the Colonists because the collectors of the new tax were all so obviously selected by nature of their willingness to climb under the Royal Governors’ desks.

Boston, long known as the seat of calm, intellectual discourse*, of course, expressed their displeasure through calm, intellectual drunken riots. As a means of debate, this worked about as well as it does now, and Parliament responded with the Punitive Acts (better known in America as the Intolerable Acts). They rescinded the Massachusetts Colonial Charter and followed that up with a number of other laws limiting mobility and trade in all of the colonies.

The response was the First Continental Congress. Delegates from all 13 colonies got together and came up with the revolutionary notion of writing a letter asking Parliament (and the King) not to be so mean all of the time. This was passed around the House of Lords, getting a good laugh like a LoLcat meme, and they doubled down by essentially announcing that the colonists, who had thought themselves full citizens of the British Empire, had exactly as many rights as meatloaf.

This angered the colonists so much that, as the 2nd Continental Congress convened, they decided to write another letter, which was quickly returned to them folded up like a used Kleenex. And that’s how we ended up on July 4th, outlining just what a douche King George was, and why we weren’t going to be his friend any more.

*My wife and I were once eating in a Boston MacDonald’s when some guy walked in and started screaming at the manager, who started screaming back, both spewing more expletives than actual words in their incomprehensible accent. This went on for five minutes until the guy left and the manager went back about his business.